IT | EN

The largest DNA study to date sheds light on Caribbean history and prehistory. By using a new method, scientists confirm that Caribbean populations have indigenous origins and therefore come from populations prior to contact with Europeans.

As reported in an article published on 23 December in Nature, an international team of geneticists, archaeologists, anthropologists, museum curators and physicists, including Fabio Marzaioli and Filippo Terrasi, respectively Associate Professor of Applied Physics and Emeritus at the Department of Mathematics and Physics of the Vanvitelli University, co-author of this study, analyzed the genomes of 263 ancient individuals (174 new and 89 previously sequenced). These individuals lived in what are now the Bahamas, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Puerto Rico, Guadeloupe, Saint Lucia, Curaçao and Venezuela.

“When Dr. Juan Aviles went to school in Puerto Rico – as reported in a recent article published on Times - teachers taught him that the original people of the island, the Taino, vanished soon after Spain colonized it. Violence, disease and forced labor wiped them out, destroying their culture and language, the teachers said, and the colonizers repopulated the island with enslaved people, including Indigenous people from Central and South America and Africans. But at home, Dr. Aviles heard another story. His grandmother would tell him that they were descended from Taino ancestors and that some of the words they used also descended from the Taino language. “But, you know, my grandmother had to drop out of school at second grade, so I didn’t trust her initially,” said Dr. Aviles, now a physician in Goldsboro, N.C. Dr. Aviles, who studied genetics in graduate school, has become active in using it to help connect people in the Caribbean with their genealogical history. And recent research in the field has led him to recognize that his grandmother was onto something.

In fact, the analyzes concerned the genetic makeup of people who lived in the Caribbean between 3,100 and 400 years before the present (1950 AD), on the basis of 45 specially produced radiocarbon dates. The data have effectively resolved several archaeological and anthropological debates, highlighting current ancestry and reaching surprising conclusions about the size of the indigenous population just before Caribbean cultures were ravaged by European colonialism starting in the 1490s.

The chronological reconstruction of events with 14C required a detailed analysis of the analyzed samples in terms of the isotopic composition of the bones. In order to obtain bias-free chronological data sets, the effect of the marine diet potentially affecting the 14C content of collagen was estimated and found to be negligible even in island areas.

This work makes the Caribbean the first place in the Americas where scientists have obtained extremely high-resolution data from ancient DNA which until now was only available in Western Eurasia. The availability of this type of analysis allows us to answer questions about the past that could not be addressed before.

Researchers found that Caribbean populations of the Archaic age are consistent with ancestry from a single population native to Central or South America, in contrast to previous research findings. The research team concluded that these archaic peoples likely had no notable ancestry with the populations of North America.

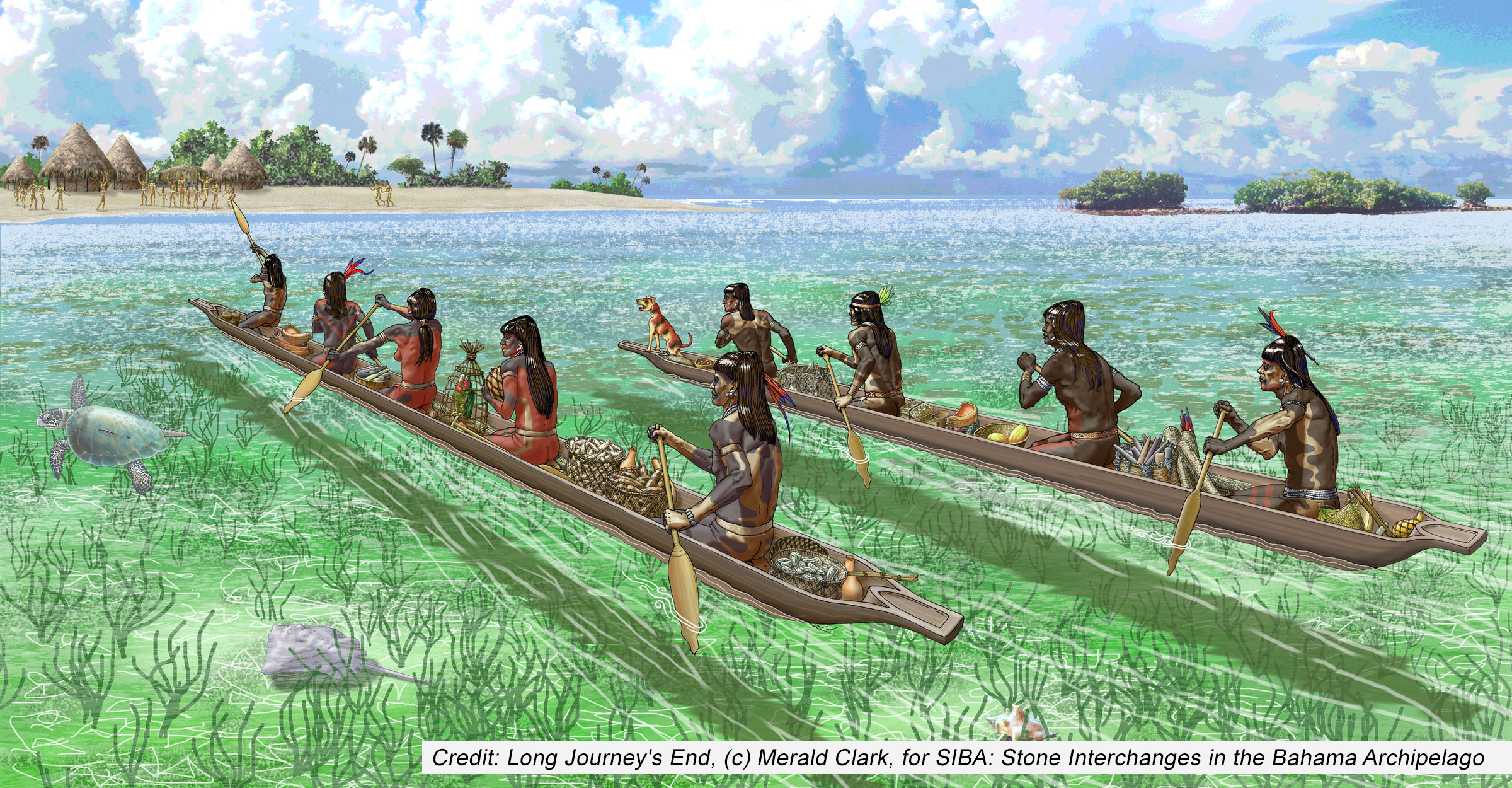

Pottery-working populations migrated to the Caribbean from South America, most likely from island to island across the Lesser Antilles, at least 1,700 years ago. When these populations began their migration they almost completely replaced the resident people who used stone tools. Only a small percentage of the archaic population remained, persistent in Cuba until the arrival of the Europeans.

Caribbean ceramic styles underwent radical changes over the next 2,000 years, before the Europeans arrived. Analyzes reveal that while pottery has evolved, population genetics has remained essentially the same in the Caribbean, century after century excluding evidence of substantial genetic contribution from continental groups and indicating that the innovation of the era of pottery is supported by an island-to-island cultural exchange rather than by the influence of waves of new people migrating from the mainland.

A new method for estimating the size of ancient populations was also introduced in this study. To the surprise of the researchers, the numbers indicate that people who lived in the combined region of Hispaniola (Haiti and the Dominican Republic) and Puerto Rico in the centuries before the arrival of the Europeans were between 10,000 and 50,000. This estimate falls far short of previous estimates and historical accounts that valued these populations from hundreds of thousands to millions of people.

The ancient Caribbean populations have left genetic traces in today's Caribbean populations, the ancestral DNA of the Caribbean today represents between 4 and 14% of that of today's population showing a time continuum in the history of Caribbean populations.

Fabio Marzaioli and Filippo Terrasi, contributed to the radiocarbon analysis and to the work on stable isotopes.